The Unyielding Coat Of Arthur

In the sunlit penal colony of Bumbleshire — a village best known for its annual fête, its three-legged ducks, and a local council run by people who failed the audition for common sense — lived one Arthur Warmly. Arthur was the sort of man who considered “compromise” a foreign word, likely French, and therefore deeply suspicious.

He was also the last known inhabitant of Britain to wear a mustard yellow coat that hadn’t been in fashion since Harold Wilson last looked pleased with himself. The coat, like Arthur, was a relic of a time when things were built to last and then stubbornly refused to die.

Arthur’s wife, Marge, had tried everything short of arson to remove it from his shoulders. “Arthur,” she’d say, in the strained tones of a woman who had long ago married for love and was now paying off the interest, “you’re sweating like a hog in a sauna. It’s July. Take the damn thing off before you poach.”

Arthur would simply grunt and adjust the collar as if donning a suit of armour before going out to joust the modern world. “Can’t be too careful, Marge. The weather turns. People catch chills. Governments collapse.”

“Not usually in that order,” she’d mutter.

The trouble truly began on the day of the Summer Fête — that annual display of scones, bunting, and community-based passive aggression. Marge, for reasons best left to therapists, had volunteered to run the cake stall, which had been generously positioned under the only tree in Bumbleshire capable of dropping sap, twigs, and bird droppings simultaneously.

Arthur, naturally, was wearing The Coat. He loitered near the Victoria sponge with the air of a man expecting battle, or at least a sudden frost.

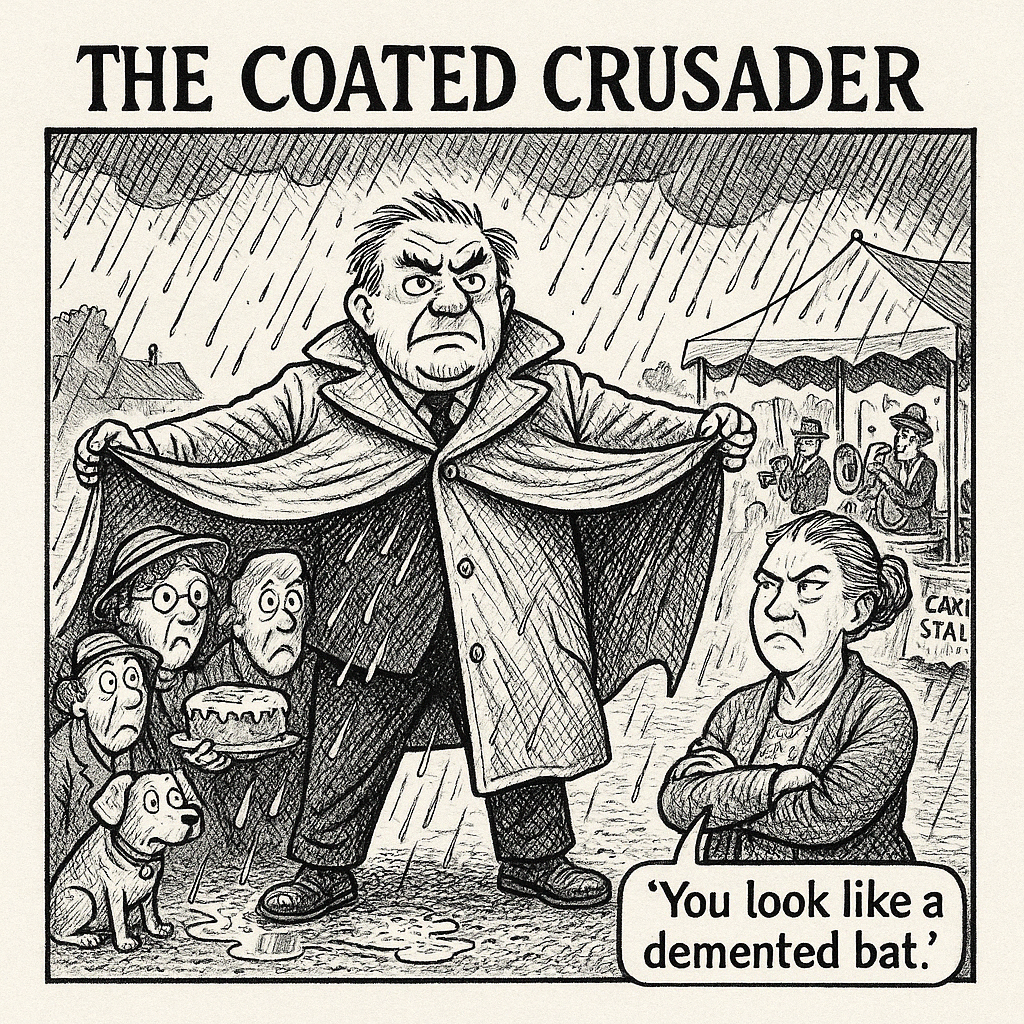

Then came the rain — thick, angry rain, the sort that turns elderly villagers into swimming instructors and causes vicars to swear under their breath.

Marge, whose cakes were now forming a flotilla headed for the cricket pavilion, shouted across the storm. “Arthur! For once in your life, help! Do something useful!”

And Arthur — lumbering, delusional Arthur — spread open his coat like some deranged, polyester-clad Moses parting the Red Sea.

“There! You see!” he bellowed, as pensioners scrambled for shelter under his outstretched flaps. “Always be prepared!”

“You look like a demented bat,” said Marge, now soaked and surrounded by a moat of Battenberg.

But Arthur stood proud, chest puffed out like a constipated pigeon, convinced he’d saved the village. And to be fair, several scones were indeed spared.

By day’s end, the incident had grown in the telling. The local paper — edited by a teenager with a thesaurus and access to clip art — dubbed him “The Coated Crusader”, and Arthur Warmly began signing autographs on napkins and bar receipts.

His coat, once the object of ridicule, was now revered. The parish council even asked him to open the new recycling bins, an honour he accepted with the gravitas of a man mistakenly knighted.

Marge gave up. There was no fighting it. The coat had won.

One night, as Arthur settled into bed — still wearing the bloody thing “just in case of night chills or burglars with a draught” — she sighed and said, “If you’re buried in that monstrosity, Arthur, I swear I’ll come back and haunt you.”

He grinned in the dark. “That’s the plan, love. You’ll never lose me.”

She lay there in silence.

And quietly began Googling industrial strength crematoriums.